Shakespeare might not have written it this way, but whether to keep going or give up, that is the actual question.

Whether someone has one miscarriage or five, a subsequent pregnancy or just the prospect of it can be downright terrifying. How do I make it through each day when each day feels like a century? What are the chances I’ll have another loss? What are the chances I won’t? When do I start trying again? And the last and most confronting question of all: how do I know when it’s time to stop?

Let’s assume in the first instance that you have decided to try again. Many patients describe a ‘yearning’ or a ‘desperation’ for another child after experiencing early pregnancy loss. I remember acutely the feeling that every single person around me was pregnant, they were all gloating about their beautiful, big, round bellies and laughing at me through their pity. Such was my intense desire to be pregnant again and have another child. Loss is one thing, but a grief fuelled by hormones can be intense.

If you’ve seen the worst that pregnancy has to offer, it’s entirely reasonable to fear it will happen again. This is why there is often a mission to ‘do things differently’ or ‘try something new’, even though, as we know, the results may be beyond our control. The loss of innocence in subsequent pregnancy, an inability to just enjoy the idea that ‘everything will work out fine’ can be incredibly painful and challenging, to say the least.

When to get going?

A miscarriage is similar to menstruation in the sense that its ultimate goal is to clear the contents of the uterus. The difference is that there are more contents to clear: the pregnancy tissue, as well as the thicker uterine lining. But the two ultimately have the same function, which is to clear the decks.

Barring any complicating factors such as, for instance, the identification of genetic abnormalities or clotting issues that would require additional medical interventions, physiologically the first and most important box you need to tick is that your miscarriage is complete and there are no signs of infection. That means either your hCG is at zero, your scans are clear or, in the case of a D&C, your treating doctor has given you clearance to try again. Once you have that, you can move onto the next stage, which is timing.

Two important studies show there may be an advantage to trying sooner, rather than later. The first was a literature review published in Human Reproduction, which showed that waiting less than six months after miscarriage to try again resulted in ‘significantly reduced’ risk of both further early pregnancy loss and preterm delivery. This contradicted World Health Organisation guidelines, which at the time the study was published in 2016 recommended waiting at least six months to try again after early pregnancy loss. When I contacted the WHO to ask for their more updated guidelines, a spokesman told me they haven’t been updated since 2005. ‘This recommendation and the underlying evidence is outdated and has not been used in more recent publications.’ The spokesman was at pains to point out that the organisation is ‘undertaking research into clinical management of miscarriage and their prevention, as well as impacts of Covid-19 infections on miscarriages’. It’s seriously disappointing the guidelines haven’t been updated, more than seventeen years after they were first published. Many clinicians, especially in developing countries, rely on this guidance for their medical practice.

Another study published in 2017 looked at 514 patients in North Carolina, Tennessee and Texas who had experienced miscarriage as their most recent pregnancy outcome. The research showed that, irrespective of race or previous pregnancies, an interval of less than three months after miscarriage was ‘associated with the lowest risk of subsequent miscarriage’. They added that ‘this implies counselling women to delay conception to reduce risk of miscarriage may not be warranted’.

You might remember that I was recommended to delay conception for two menstrual cycles after my first loss. And this research begs the question why. The answer is simple: no pregnancy outcome is ever assured. Even if you’ve lived through one loss, it doesn’t mean you’re prepared for another. Before you try again, you have to be ready for whatever might happen. So no matter what the statistics say in terms of physical outcomes, there’s no point rushing in unless you’re mentally ready for another pregnancy and all that entails.

Time has to be taken to ensure you have the right supports around you; whether that is medical professionals, family or friends.

Likelihood of success

The data around the statistical likelihood of carrying a pregnancy to term after miscarriage is nothing like what you’d expect. It’s actually exceptionally positive. It’s baffling that medical professionals, including GPs, midwives and obstetricians, do not make this information more publicly available or understood. That’s not to say that none do, of course. Just that it’s not broadly understood or known among the general population. If this was to shift, it wouldn’t just encourage patients to try again, but also help them emotionally prepare for a subsequent pregnancy, if they choose to try for one, with a more optimistic or hopeful lens through which to look.

So here is the data. After one miscarriage, there is absolutely no reason to think your next pregnancy will not be successful, and that’s why doctors are so eager to encourage patients to ‘just try again’. But surprisingly, even after multiple miscarriage, odds are likely that if you can conceive you will have a pregnancy resulting in a live birth, though it is important to note that these statistical likelihoods do decrease sharply with age.

For ‘idiopathic’ miscarriage, meaning losses with ‘no apparent cause’, at the age of twenty, even after two miscarriages, your likelihood of success in a subsequent pregnancy is 92 per cent. That comes down to 89 per cent at twenty-five, 84 per cent at thirty, 77 per cent at thirty-five, 69 per cent at forty and 60 per cent at forty-five.308 Let me clarify: even at forty-five years of age and having had two miscarriages, there’s a better than 2 in 1 chance that you will have a successful live birth.

Those stats decline, but stay higher than I think many would expect, even as the number of previous miscarriages and ages increase. At the other end of the spectrum, even after five idiopathic miscarriages, your likelihood of a successful pregnancy at twenty is still around 85 per cent. Again, it comes down with age, but remains surprisingly high; 79 per cent at twenty-five, 71 per cent at thirty, 62 per cent at thirty-five, 52 per cent at forty-two and 42 per cent at forty-five.309 And those odds, all things considered, really ain’t bad.

Gettin’ jiggy

Sex after loss can be incredibly challenging. Or it can be just what you need. There is no right answer. In terms of trying again, conception through sexual intercourse can be a very different ballgame when one or both partners are mourning a loss. One or both partners might not even have a sex drive, which can be dampened by fear, anxiety or depression. The birth partner can also be experiencing a degree of dissociation from or distrust in their body, due to a (misplaced) feeling that it may have ‘failed them’ in a previous pregnancy.

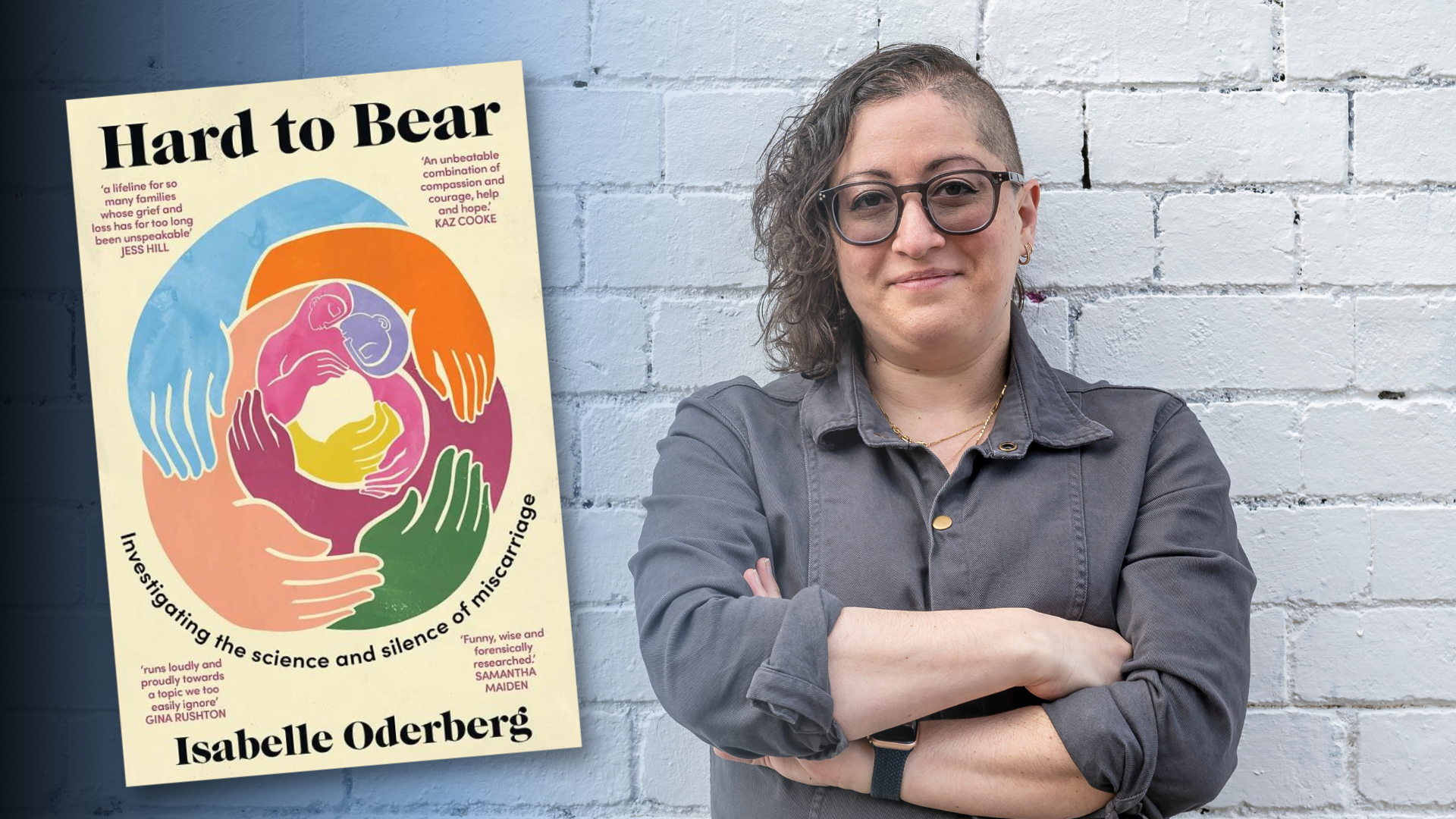

This is an extract from Hard to Bear: Investigating the science and silence of miscarriage by Isabelle Oderberg, out now from Ultimo Press, available in all good book stores. This work was made possible by the Victorian Women’s Benevolent Trust through a grant to the Jean Hailes Foundation.

After growing up in Hong Kong, Isabelle Oderberg went to university in Melbourne. She has worked as a journalist for two decades in newswires across Europe, Asia and Australia, where she was the country’s first social media editor for Melbourne’s Herald Sun. Her work has appeared in The Age/SMH, Guardian, ABC, Meanjin and elsewhere. She also worked as a media and communications strategist across the not-for-profit sector. Hard to Bear is her first book.

After growing up in Hong Kong, Isabelle Oderberg went to university in Melbourne. She has worked as a journalist for two decades in newswires across Europe, Asia and Australia, where she was the country’s first social media editor for Melbourne’s Herald Sun. Her work has appeared in The Age/SMH, Guardian, ABC, Meanjin and elsewhere. She also worked as a media and communications strategist across the not-for-profit sector. Hard to Bear is her first book.