In the past decade, some Indian women in Australia have been dying in ways that have left the Australian-Indian community shocked and searching for answers. Of a cluster of suicides in a small area of Melbourne—seven of them in total—more than half had contacted police for family violence.

One woman per week is killed in Australia by a current or former intimate partner. Our Watch, the peak Australian body charged with prevention of the deadly problem, labels family violence a serious problem in Australia. It touches all segments of society, and never fails to shock.

Previous reports of murder-suicides reported in 2012 to 2016 were once again under focus in 2022, when Raj Sharma was charged with the murder of this wife Poonam Sharma and their six-year-old daughter Vanessa. A series of murders, then, of women and children in Victoria by the men they loved and who were meant to love them. Why were women and children dying in domestic violence episodes? The Indian community was in shock.

Indian and South Asian women share many experiences with women across the world, but their lives are also different in significant and unique ways. It is in these differences that answers and solutions can be found. Answers and solutions that will make the lives of this group better. Answers and solutions that will keep them alive.

Exposure to industrialisation and modernisation is changing India, and with it, the lives of Indian women. They are better educated than their mothers, and wealthier. But sociologists and academics are curious: will modernisation benefit the status of Indian women? Will they continue to be the subjects of traditional societal gender roles of modesty and submission, or will we see a change in women’s position in the family and society?

More than twelve years ago, I began my work supporting victim-survivors of domestic family violence in Australia. The most hard-hitting stories kept coming—transnational abuse, dowry exploitation, economic exploitation, domestic servitude, and sexual exploitation. How could these things be stopped? To answer this question, I had to find answers to many others. What makes women travel to Australia? What are the roles of globalisation, culture, migration, acculturation stress, the pressures of moving into a new country? My passion to find answers was sustained by the parents of victim-survivors, many of whom had travelled from India to Australia to support their daughters and were themselves often suffering from extreme distress, insomnia, clinical depression and anxiety triggered by the pain of what their daughter had been through. Marriage is an essential, defining moment in many women’s lives, but it’s not always a happy one, be it in India or elsewhere in the world—including Australia.

When I came to Australia in the early 1970s as a young wife, I had some idea that Australia would be very different to India. But I did not know how different. In Australia, that women talked to men or vice versa was simply not noteworthy. There was no concept of shame and dishonour for the family, only accountability to oneself.

But it also dawned on me that Australia has its own deep work to do regarding racism and colonisation. Family violence is still present. In Australia it touches 1 in 4 women, and 1 in 13 men suffer partner abuse. One woman per week is killed by an intimate partner. Violence against women is a wicked global problem, not confined to any class, religion, and country. The question is what tools or tactics are used, by whom, and in what context.

It is a privilege to be a psychiatrist. Every day I learn about humanity from the vantage point of an insider. Though I listen to unimaginable stories of trauma and abuse suffered by my patients, my patients have also taught me about human resilience and strengths and the myriad ways in which they find inner power to survive.

Change is inevitable—it always comes. So how do we prepare for it? How do we manage the process of it? Those who stand rigidly in the face of change are liable to damage themselves—as an old hardwooded tree that does not bend in a storm will break, but a green tree that does bend is spared the storm’s ravages. An engineer patient of mine said that this principle is used in the construction of highrise buildings: the taller the building, the more it needs to be able to sway with the wind.

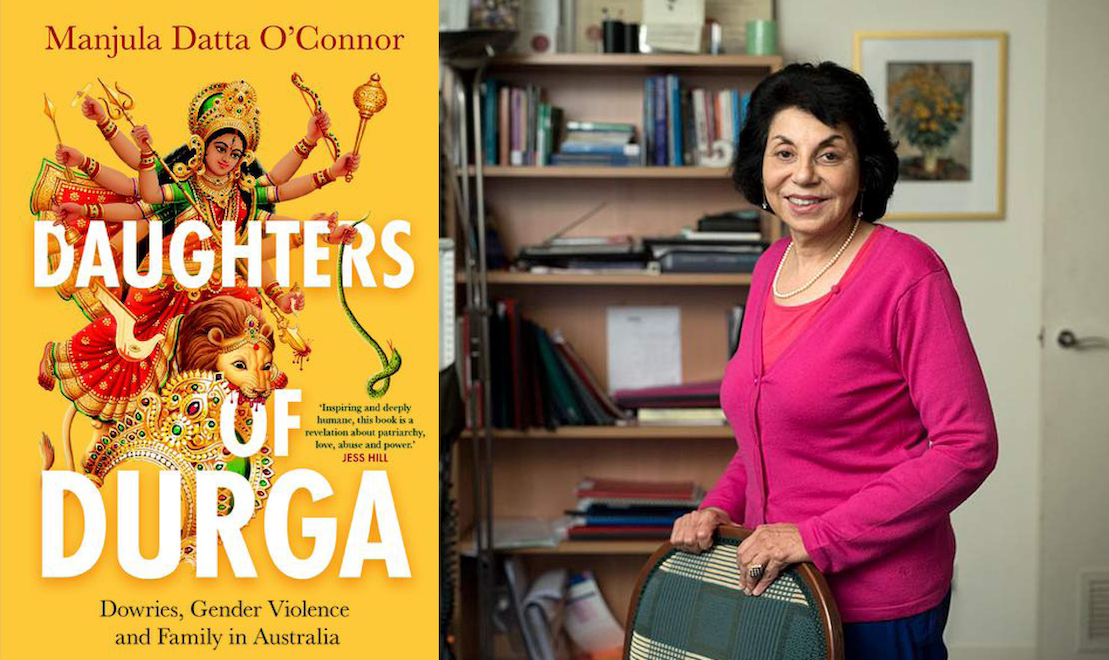

This is an edited extract from Daughters of Durga: Dowries, Gender Violence and Family in Australia by Manjula Datta O’Connor, available now (MUP).

Dr Manjula O’Connor is a Clinical Psychiatrist and Chair of the Family Violence Psychiatry Network of the Royal Australian New Zealand College of Psychiatrists. She is Hon Senior Fellow at the Department of Psychiatry University of Melbourne. Dr Manjula has a longstanding interest in migrant women’s mental health and family violence. She is a clinician, researcher, reviewer of journals, advocate and works closely with community in prevention of family violence.

Dr Manjula co-founded the AustralAsian Centre for Human Rights and Health and led public dowry abuse campaign in Victoria that became Australia wide, converted to legislation in Victoria, and recognised in the Fourth National Plan against family violence in Australia. Her current project is around suicide prevention and enhancing mental health literacy in South Asian communities.

Dr Manjula received the Victorian Government Multicultural Award of Excellence in Women’s Health-2012 and she has been recognised in Victorian Parliament and Federal Australian Parliament on multiple occasions.