Did you know that the echidna was named after an ancient Greek demon who was half woman and half snake? The European naturalists who christened the species this way encountered an egg-laying mammal with two vaginas and a massive brain, triggering their deepest primal fears of female and reptilian mysteries, personified in a monstrous chimera of western mythology. Woman and snake have always inspired awe in the human imagination, an awe that turned to vengeful wrath the day they stole a piece of fruit from a Middle Eastern garden. After that, things went sideways and men broke the world, smashing the old stories and burying the fragments deep.

Nobody is happy with how all that turned out, and everybody longs to make their culture great again. Perhaps we should do some narrative archaeology to unearth ancient tales that might inspire us to discover a better world together. Not in a scholarly way—it should be an exciting and sexy quest like in the movies, full of heroes and villains, exotic locations and funny (but wise) native guides.

Imagine you are an adventurer, following clues and fighting unscrupulous rivals in a desperate race against Nazis and wealthy super villains to claim the fabled secrets of supreme ancestors, the treasures of legend, to shape the course of history. X marks the spot, encrypted in crumbling papyrus and etched stone, the secret locations of truths and proofs to be preserved, suppressed or weaponised— depending on who gets there first. You unsettle forgotten tombs and lost ruins, seeking answers in the crowns of warrior queens, in the notched bones of giant animals long extinct, in the dusty journals of rogue scholars and bearded mystics. But beware: there be dragons here, and writhing multitudes of hissing creatures lurking in the dark.

Snakes. Why did it have to be snakes?

Beneath your intrepid boots, reptilian mythologies echo from a time before truth, from an age undreamed of, long before the temple-builders, hoarders and ideologues invented vengeful gods to keep their women at home and prevent their teenagers from masturbating. It was an age when we thrived within our biological niche as a custodial species of the land and sea. There’s a rustle in the dry grass of history, in this breathless moment before a random lightning bolt or tossed cigarette may set the whole world alight. The old stories, the ones from before the hero’s journey began, the half-remembered stuff of ayahuasca trips and nightmares—these take you back to the old ways, and the old ways all have sacred Snakes at their foundation. (It seems appropriate to capitalise the names of the great Serpents as we continue, as people do with all spiritual entities that are held sacred.)

There is no paragon of wisdom who holds all the Serpent knowledge today, but that’s okay; nobody knows much about anything alone. Collectively, though, our kin across different tribes carry knowledge about this skin shedder, fast striker, egg-layer, land and water mover—this silent and hidden keeper of secrets.

Basilisk, Wyvern, Naga, Goorialla, Quetzalcoatl and many others connect all this serpentine wisdom across a pluriverse of creation entities, entangling languages, flames, skies, waters and rocks. Let us bring all our stories, fears and fascinations to the campfire and see what we can know, all together in one circle. You can’t sit in front of the fireplace, though—only beside it—because there is no wall or chimney and there are people on the other side, so there can be no ‘front’. Their faces are distorted by heat and smoke, but so is yours. The view from alongside is the only one that is clear when the fire is too big, so come alongside us. We’ll use this Anglo trade dialect we share, making pop culture references from time to time from songs and stories that we may have in common, so we can come into good relation together. Maybe you’re not a rugged adventurer after all. You might be happier as a diplomat making cultural embassy, exchanging knowledge with Xhosa, Zhongguoren, Danes, Murris, Nepali, Ma¯ori, Celts, Persians and more.

Who do you belong to? Us-two belong to our lands, children, families and each other—an Aboriginal mother and father from Barada and Kapalbara people in Central Queensland and the Apalech clan from Wik Country further north on Western Cape York, entangled with fraught affiliations from Nungar, Pama, Murri and Koori Country, among what our community calls ‘Lost Mob’. This means we are bound up with many ancestors and descendants from families beyond our reach and memory, displaced by invaders, seeds scattered tragically but still sprouting fiercely all over, from Palm Island in the north to Kangaroo Island in the south of this continent (which is currently named Australia).

Aunty Munya Andrews, an Elder from the Bardi of Western Australia, told us that the continent used to be called Bandaiyan and that it is the body of a giant ancestor with both male and female genitalia. There are many names and stories, but we don’t argue about these things, because we all agree that there are great Serpents running through the living body of this land as threads binding Our Serpent Relations us together in a patchwork quilt of bio-cultural diversity, crisscrossed with ancient ceremonial paths and trade routes. Before the Federation of Australia, this vast Indigenous network extended across the sea in trade with Asia and Melanesia. But the continent has a flag now, and its shores are surrounded and isolated by imaginary lines that we may not cross without a passport.

Protocols of traversing territories and waters for trade, for Ceremony and for embassy still exist for us in the old ways that endure: Sunrise-Sunset Dreaming traditions in which our governance expands in concentric sovereignties from self to pair, to family, to clan, to tribe, to region, to continent and beyond. This is embedded in our languages, with pronouns we translate as I-in-relation, us-two, us-only and us-all. We cannot speak without naming our roles in this relational system of governance. So we’re gradually naming these roles and pondering the yet unclear lines of connection that exist between us-two and you-all, stretching across lands and waters and time.

We’re comfortable with that uncertainty—in our old protocols of embassy we just let understanding emerge as we share story together. Our thinking-feeling processes take a lot longer than the usual acknowledgements, welcomes, introductions and lessons people expect in modern rituals of knowledge exchange. There are no questions or demands for clarity in our way. If we don’t know the difference between Law and Lore, for example, we don’t seek a glossary or Q and A session; we just listen and wait for the context of stories and relationships to shape our understanding.

We are writing this from the lands of the Kulin First Nations in the south-east of the continent, where we have sat patiently for years in these contested territories and stories, slowly coming to understand the Lore of Bunjil—the sacred knowledge of the creator as an eagle, who made the land in partnership with a great Serpent. That Serpent became the Law in the land, which we understand in our traditions as a flow that governs the complexity of right relations in living systems. We respect this deeply, as well as many more stories that seem to contradict each other, but make sense in the overall weave of Lore. Goodithulla (the Barada eagle), a totemic entity in our family, comes alongside Bunjil’s Lore, while the Law of the Serpent we honour helps us align with the Law in the lands of Kulin Peoples. In this way we have made kin, worked for community and gained permissions to do our far-reaching thinking, making and Ceremony here.

Data is always incomplete, so good thinking involves feeling through what is revealed when we gather in shared sites of meaning. That’s how all human beings learn the inexplicable complexities of culture—through intuitive connection rather than prefabricated information. We’ve already been way too heavy on the exposition here, so let’s get back to the business of sharing the nature of our relationship in the storyscape of Serpents that holds our world together. Our Serpent Relations7

As parents and spouses, we’re a kin pair, and there is Law for that relation nested in the fabric of creation, carved and woven through Serpent Lore: Thaypan (taipan entity) and Kabul (carpet python entity) entwining ancestral lines sung between sacred sites. They shape the shifting landscape, its signals and essences, and the ngeen wiy which is the spirit unseen within and all around. They keep regenerative life and death cycles spinning in closed loops of creation and destruction, man and woman, joined across open loops of entropy and sustenance between worlds. One entity’s kaka is another entity’s lunch. First man, first woman, child. Two snakes. One big story—the reason we don’t collapse into a void of non-being.

That old Lore was the dream us-two dreamed the night before our hands first met at a campfire, elliptical orbits of our gendered roles overlapping as man gathers wood and woman keeps the flame. In the dream, we were taller than trees and made of southern lights, walking as the original man and woman did at the birth of the custodial species now called human, by some. But, oh! Dreaming is one thing—colonial reality is another entirely!

In the waking world, a trafficked carpet snake trapped in a terrarium nearby butted its head frantically against the walls of its prison, over and over in the rhythm of our Ceremony, until the glass cracked and the storm that threatened our fire split down the middle and passed on either side of us. From our mother-side and in-law mobs, the old 8

Kapalbara carpet snake men from the north called out, and we sang back, then—snap!—we woke to the nine-to-five schedules of a world in pain. There is no memory left to us of how that dream ended, only a sense that together we were destined to be more than we had become, that we would do something wonderful to sustain creation, one day.

Life isn’t a dream, though, and sublime visions don’t put food on the table unless you’re leading a cult. A decade later, we wonder if we were mistaken, if perhaps there was no great spiritual destiny for us at all, only dirty nappies, bigotry, violence, bills and grief. Well, maybe it isn’t great stories and heroes’ journeys that change the world—maybe it’s the little things.

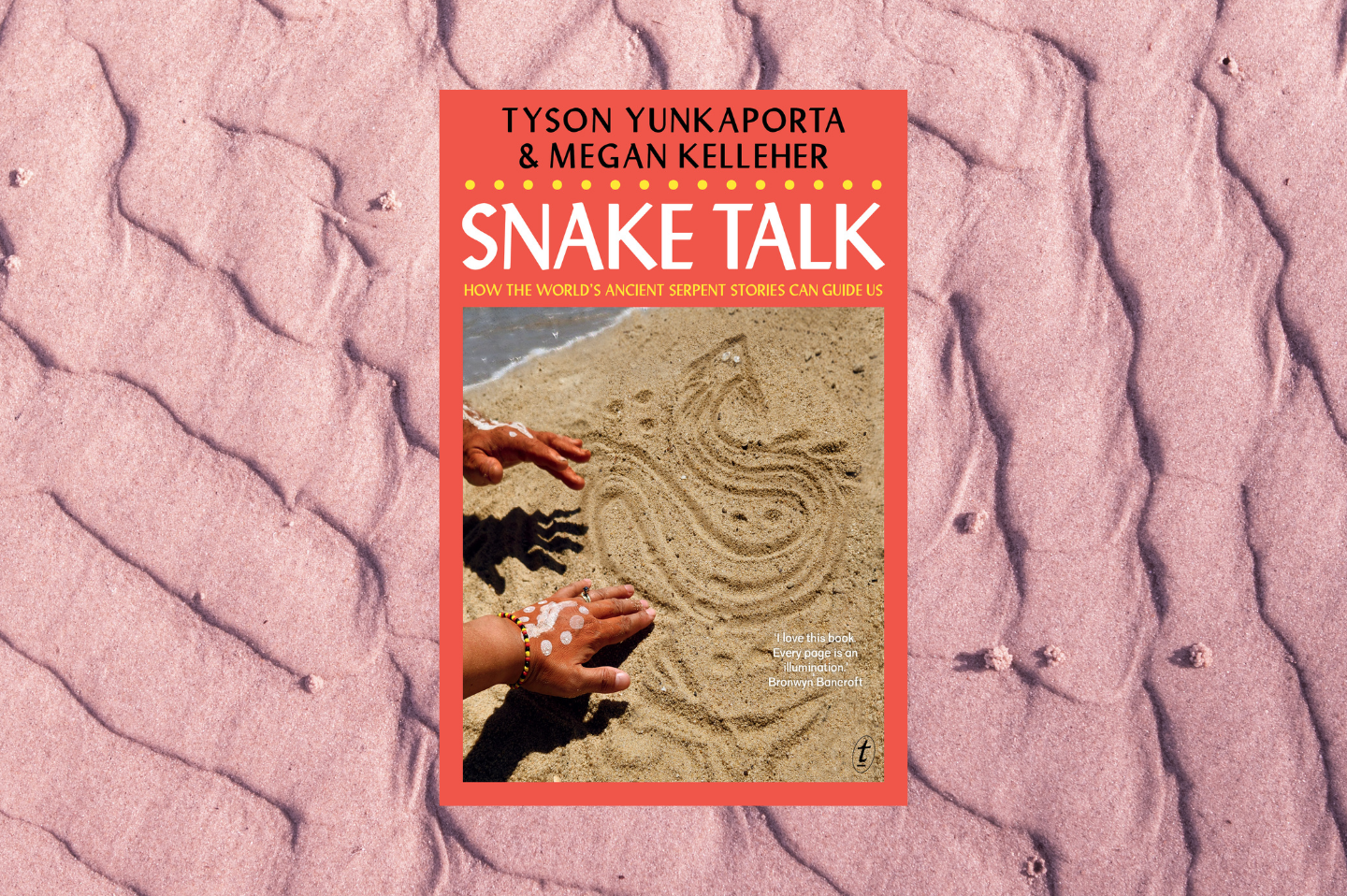

Image: Nicholas Walton-Healey

Image: Nicholas Walton-HealeyThroughout Snake Talk, authors Tyson Yunkaporta and Megan Kelleher yarn with Indigenous Elders from across the globe to find out what unifies us through this symbol of regeneration, fear, and connection. Snake Talk features the Rainbow Snake, the Irish Wyrm, Viking Dragons, and Nagas/Naginis, among many others.

Tyson, Megan’s partner, is the renowned author of Sand Talk, which was published to critical acclaim in 2019.